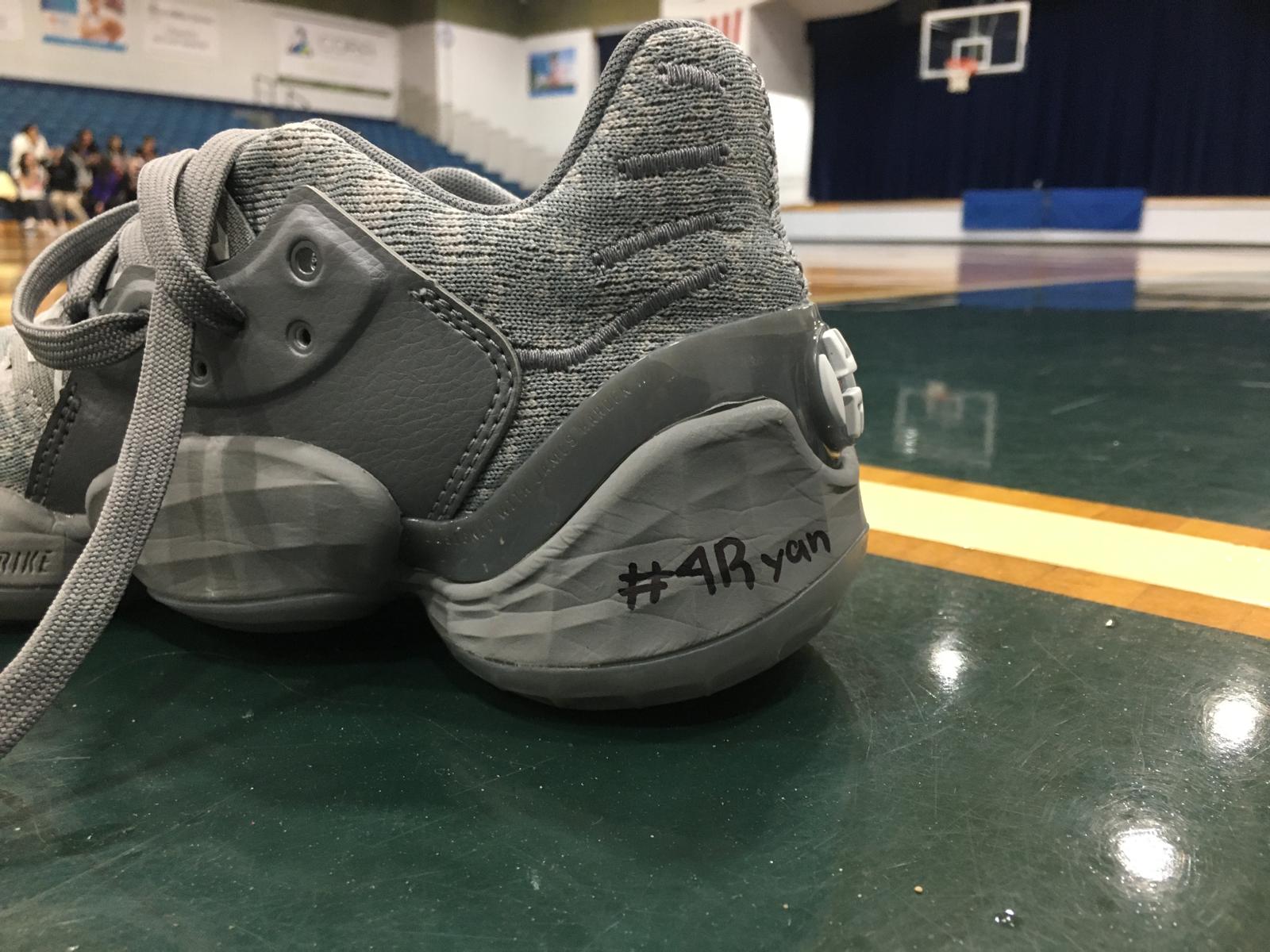

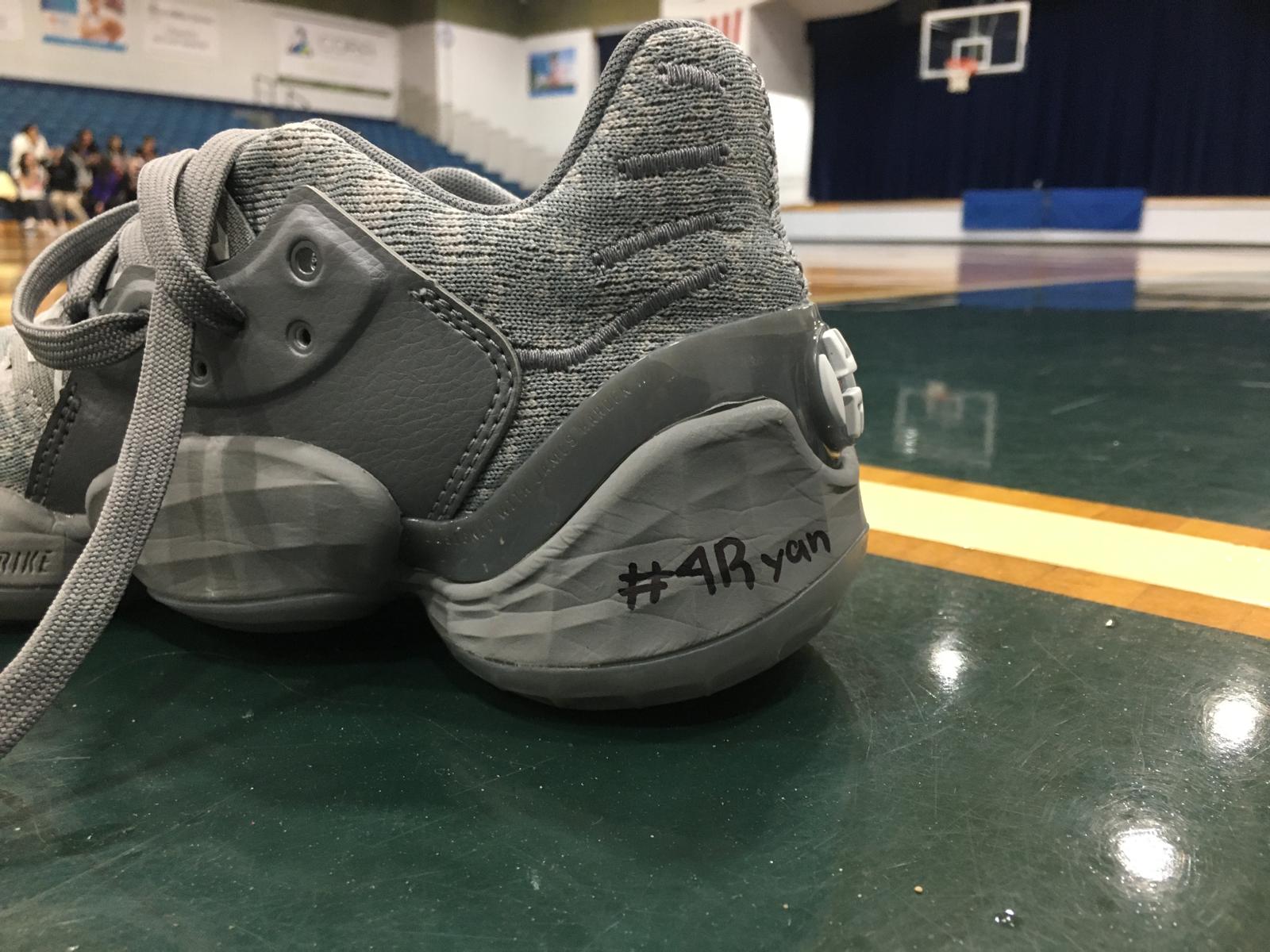

Florida Christian girls’ basketball team dedicating season to coach’s son. Here’s why

Florida Christian girls’ basketball team dedicating season to coach’s son. Here’s why

© Copyright Grief To Purpose 2026

Powered by Grief To Purpose

© Copyright Grief To Purpose 2026

Powered by Grief To Purpose